Case 22 Discussion

Learning Objectives:

- Generate a differential diagnosis for linear colonic ulcers.

- Describe clinical features of microscopic colitis.

- Select appropriate therapy for a patient with microscopic colitis

IBD EPAs Covered:

EPA 1: Classify IBD phenotype, disease activity, and extraintestinal manifestations

EPA 2: Use advanced diagnostic and therapeutic endoscopic and radiographic techniques in the management of IBD

EPA 3: Prescribe and manage evidence-based IBD therapies using clinical pharmacologic principles in clinical practice

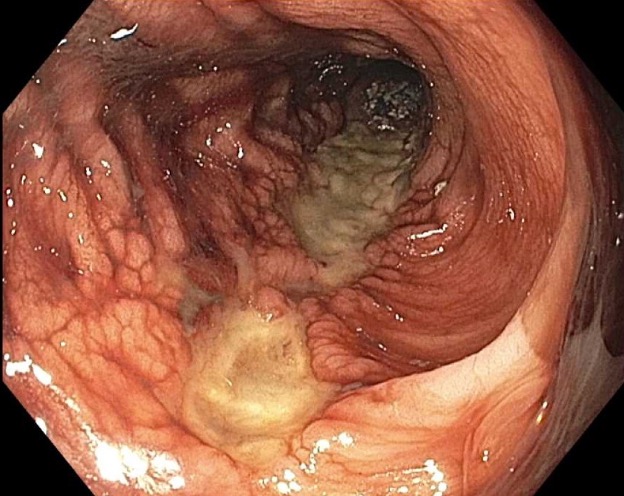

The differential diagnosis for linear colonic ulcers includes Crohn’s disease and ulcerating colonic infections, such as tuberculous colitis and cytomegalovirus colitis. In these cases, however, serpiginous or cobblestoned appearance of the ulcers would be more typical than a strictly linear ulcer.

Collagenous colitis is a type of microscopic colitis, along with lymphocytic colitis. Both forms of microscopic colitis typically present with chronic watery diarrhea, which may be associated with urgency, nocturnal stools, and abdominal pain. It has been associated with other autoimmune conditions, including autoimmune thyroiditis, type 1 diabetes, inflammatory arthritis, and uveitis. Patients with celiac disease have an increased risk of microscopic colitis, and this should be considered in patients with celiac disease experiencing persistent diarrhea despite adherence to a gluten-free diet. The peak age of onset is in middle age and there is a higher incidence in those assigned female at birth.

Certain medications have been implicated in the development of microscopic colitis, including non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, proton pump inhibitors, and selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors. However, the pathophysiologic role of these agents in the development of microscopic colitis has not been determined. Immunotherapy agents may cause microscopic colitis as one manifestation on the spectrum of immune checkpoint inhibitor colitis. Smoking has also been associated with increased risk of microscopic colitis, as well as earlier age of onset.

The endoscopic appearance of the colon is typically normal in microscopic colitis, although edema, erythema, and friability have been described. However, collagenous colitis has been described in several case reports as presenting with linear ulcerations. In some cases, these have been deep enough to result in colonic perforation. Clinically, some of these patients have presented with abdominal pain and bloody stools, akin to the classic presentation of colonic ischemia. On histology, microscopic colitis is characterized lamina propria mononuclear infiltrates, with ≥ 20 intraepithelial lymphocytes per 100 surface epithelial cells used as a cut-off for the diagnosis of lymphocytic colitis. Collagenous colitis is characterized by a thickened subepithelial collagen band ≥ 10 micrometers in diameter. Histologic findings suggestive of microscopic colitis but not meeting either of these criteria are designated as “incomplete microscopic colitis” or “microscopic colitis not otherwise specified.”

The primary goal in management of microscopic colitis is clinical remission. Histologic remission does not appear to be necessary. Indeed, mild cases can be effectively managed by an anti-diarrheal such as loperamide alone. According to the 2016 AGA guideline, for patients with more active disease, budesonide is the first-line treatment for induction of remission. The typical course is 9 mg per day for 8 weeks followed by a taper. Possible second-line treatments given conditional recommendations include cholestyramine, bismuth subsalicylate, mesalamine, and prednisone. There seems to be an increased rate of concurrent bile acid malabsorption in microscopic colitis, though the reason for this is unclear as the ileum is usually unaffected. These alternative treatments may be considered for patients with persistent diarrhea despite budesonide, or for whom budesonide is not feasible. While repeat colonoscopy to document histologic remission is not generally required, it may be helpful in cases of persistent diarrhea, as histologic remission in such cases may point towards an alternative explanation for diarrhea such as irritable bowel syndrome. Documenting endoscopic improvement is likely warranted for cases where there are overt endoscopic findings at presentation, such as the ulcers in this case. For some cases of severe refractory microscopic colitis, biologics (such as anti-TNF agents or vedolizumab) or immunomodulators have been described. In patients who respond to budesonide, symptomatic relapse is common after withdrawal of initial therapy. In such cases, budesonide maintenance therapy is recommended at the lowest dose that controls symptoms, and a re-trial of treatment discontinuation should be considered after 6-12 months. Although budesonide has low systemic bioavailability due to extensive hepatic first pass metabolism, prolonged use has been associated with bone loss, and osteoporosis screening and treatment should be performed in patients who require prolonged therapy.

References