Case 14 Discussion

Learning Objectives

- Select the appropriate endoscopic grading criteria for inflammatory bowel disease

- Explain risk factors for development of CRC in patients with IBD

- Understand dysplasia surveillance intervals for patients with IBD

- Apply practice recommendations based on the SCENIC trial for use of chromoendoscopy in dysplasia surveillance

IBD EPAs

EPA 2: Use advanced diagnostic and therapeutic endoscopic and radiographic techniques in the management of IBD

EPA 4: Manage adverse events and complications of IBD and IBD therapies

EPA 10: Apply preventive health strategies for patients with IBD

Endoscopic scoring systems for both ulcerative colitis and Crohn’s disease as well as postoperative Crohn’s disease can aid in the reporting of endoscopic findings and assessing endoscopic severity of disease. None of these scoring systems has been accepted as the standard, and preference of one system over another remains at the discretion of the practitioner. Consistent among these scoring systems are descriptors that should be included in all endoscopy reports to aid in clinical decision making, which include extent of disease, continuous involvement versus skip areas of involvement, and the presence of erythema, granularity, friability, erosions, ulcerations, and loss of vascular pattern (in CD, by colonic segment).

The Mayo score is used to assess severity of disease activity in patients with known ulcerative colitis, particularly when considering changing, adding or stopping a UC medication. The Mayo score is the most commonly used scoring system for UC in clinical trial and routine practice.

Factors that heighten the risk for IBD-associated dysplasia and colorectal cancer include degree of inflammation, extent and duration of disease, family history of colorectal cancer, concomitant primary sclerosing cholangitis (PSC), young age at diagnosis and presence of strictures. Per the American Gastroenterological Association Clinical Practice Update on Endoscopic Surveillance and Management of Colorectal Dysplasia in Inflammatory Bowel Diseases (AGA CPU) from 2021, initial screening for dysplasia should be performed at 8-10 from diagnosis as well as immediately following diagnosis of PSC. At this study, biopsies should be taken of multiple colonic segments to help guide future surveillance intervals. Dysplasia surveillance should ideally be done with inflammation controlled, adequate bowel prep and high definition endoscopes [10]

Targeted biopsies should be taken of regions suspicious for dysplasia. Endoscopic resection should be performed where there are clearly demarcated lesions. If not using spray chromoendoscopy, virtual chromoendoscpy is a suitable alternative per the AGA CPU. If not using either of these modalities, 4 adequately spaced biopsies every 10cm should be taken of regions previously affected by colitis and also of prior dysplasia. Targeted biopsies of representative or concerning pseudopolyps is appropriate during colonoscopy. Surgery should only be considered as a last resort for managing CRC risk in the setting of severe pseudopolyposis. [10]

Should invisible dysplasia be found on random biopsies, the initial management step for surveillance is to refer the patient to an experienced endoscopist with chromoendoscopy expertise to assess subsequent decisions regarding endoscopic resectability of a lesion with surveillance colonoscopy versus colectomy. Further confirmation by an expert GI pathologist in IBD and a second pathologist is recommended before making a management decision.

The SCENIC trial determined that colonoscopy using chromoendoscopy is the optimal endoscopic surveillance strategy to detect dysplasia [1,2]. Chromoendoscopy uses a dye solution of either methylene blue or indigo carmine applied onto the colonic mucosa to enhance contrast during surveillance colonoscopy. In a meta-analysis of eight clinical trials of surveillance colonoscopy, chromoendoscopy detected a significantly greater proportion of patients with dysplasia in comparison with white light colonoscopy (relative risk (RR), 1.8 [95 %CI, 1.2–2.6] and absolute risk increase, 6 % [95 %CI, 3–9 %]). In the four tandem studies of the meta-analysis, in which each patient had both a chromoendoscopy and white light examination, the number of visible dysplastic areas almost doubled (RR, 1.9; 95 %CI, 1.4–2.7) with chromoendoscopy. The value of chromoendoscopy in the detection of dysplasia beyond high-definition colonoscopy has been a point of contention. High definition endoscopy provides image signals of higher pixel density than standard-definition. Based on a prospective trial that showed the significant benefit in dysplasia detection using chromoendoscopy (21 %) compared to high definition white light alone (9 %), p=0.007, the SCENIC guideline suggested the use of chromoendoscopy even when using high definition white light colonoscopy [3].

Since the SCENIC publication, a prospective randomized controlled trial further supports the significant value of chromoendoscopy in IBD surveillance colonoscopy to detect more dysplasia compared to white light high definition colonoscopy [4]. Currently available equipment-based image enhancement technologies include narrow band imaging (NBI) (Olympus, Tokyo, Japan), i-scan (Pentax, Tokyo, Japan), and Fuji Intelligent Chromo Endoscopy (FICE) (Fujinon, Tokyo, Japan).

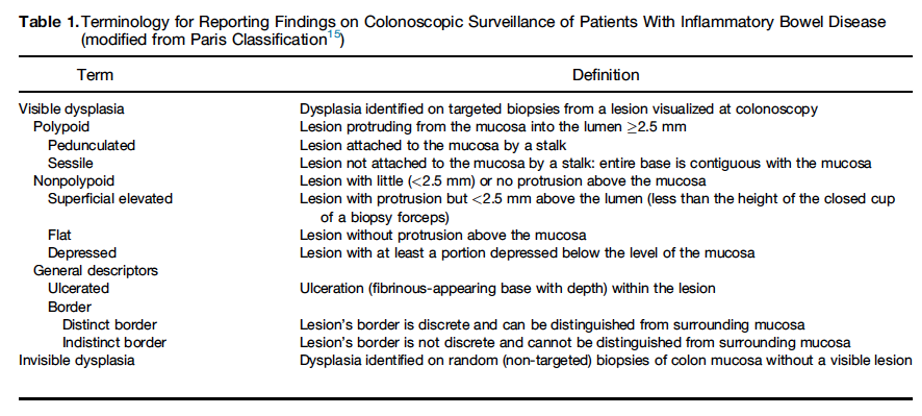

The AGA CPU uses a modification of the Paris classification system described in the SCENIC trial to describe lesions found on colonoscopy (see table below). Visible lesions can be further characterized as polypoid (sessile or pedunculated), which protrude by 2.5 mm or more into the lumen, and nonpolypoid (flat or depressed), which are < 2.5 mm into the lumen. In addition, the presence or absence of a distinct border is a critical feature to describe to assess the feasibility of complete endoscopic resection. The term “ endoscopically resectable” is defined as a lesion with identifiable distinct margins, appears to be completely removed on visual inspection after endoscopic resection, and completely removed on histologic examination [10].

Laine L, Kaltenbach T, Barkun A, et al. SCENIC international consensus statement on surveillance and management of dysplasia in inflammatory bowel disease. Gastroenterology 2015;148:639-651 e28.

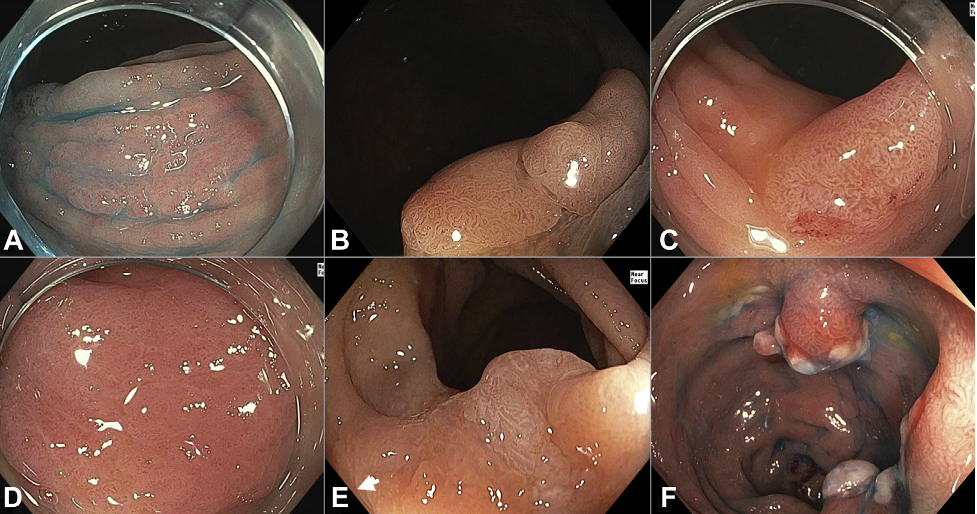

Endoscopic features of dysplasia. A, Superficially elevated morphology accentuated with chromoendoscopy. B, Nonpolypoid dysplastic lesion with vascular and surface pattern of neoplasia. C, Focal friability. D, Uneven erythema. E, Villous mucosa. F, In contrast, pseudopolyps have an inflammatory appearance often with exudate.

The AGA CPU recommends surveillance colonoscopy rather than colectomy after complete removal of nonpolypoid dysplastic lesions. After negative screening colonoscopy, the AGA CPU recommends surveillance every 1-5 years based on individual patient risk for CRC. Pouch surveillance should be performed annually in those at high risk of CRC and at individualized intervals for those at lower risk.

References:

- Eaden JA, Abrams KR, Mayberry JF. The risk of colorectal cancer in ulcerative colitis: a meta-analysis. Gut. 2001;48:526–35.

- Friedman S, Rubin PH, Bodian C, et al. Screening and surveillance colonoscopy in chronic Crohn’s colitis: results of a surveillance program spanning 25 years. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2008;6:993–8. quiz 953–4.

- Friedman S, Rubin PH, Bodian C, et al. Screening and surveillance colonoscopy in chronic Crohn’s colitis. Gastroenterology. 2001;120:820–6.

- Laine L, Kaltenbach T, Barkun A, et al. SCENIC international consensus statement on surveillance and management of dysplasia in inflammatory bowel disease. Gastrointest Endosc. 2015;81:489–501. e26.

- Laine L, Kaltenbach T, Barkun A, et al. SCENIC international consensus statement on surveillance and management of dysplasia in inflammatory bowel disease. Gastroenterology. 2015;148:639–651 e28.

- Picco MF, Pasha S, Leighton JA, et al. Procedure time and the determination of polypoid abnormalities with experience: implementation of a chromoendoscopy program for surveillance colonoscopy for ulcerative colitis Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2013;19:1913–20.

- Mohammed N, Kant P, Abid F. High definition white light endoscopy (HDWLE) versus high definition with chromoendoscopy (HDCE) in the detection of dysplasia in long standing ulcerative colitis: a randomized controlled trial. Gastrointest Endosc. 2015;81:AB148.

- Rao AK, Soetikno R, Raju GS, et al. Large Sessile Serrated Polyps Can Be Safely and Effectively Removed by Endoscopic Mucosal Resection. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2016;14:568-574.

- Moss A, Bourke MJ, Pathmanathan N. Safety of colonic tattoo with sterile carbon particle suspension: a proposed guideline with illustrative cases. Gastrointest Endosc 2011;74:214-8.

- Murthy SK, Feuerstein JD, et al. AGA Clinical Practice Update on Endoscopic Surveillance and Management of Colorectal Dysplasia in Inflammatory Bowel Diseases: Expert Review. Gastroenterology. 2021 Sep;161(3):1043-1051.e4. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2021.05.063.